Central Asia has long been viewed through the lens of imperial conquest and Soviet social engineering. But its history is far more complex. In this interview, historian Adeeb Khalid, author of the landmark books Making Uzbekistan and Central Asia: A New History from the Imperial Conquests to the Present, discusses the legacy of Russian and Soviet rule in the region, and why narratives of colonialism, nation-building, and geopolitical intrigue continue to distort how Central Asia is understood today.

- 1. Was Central Asia a Colony?

- 2. Soviet Empire—or Something Else?

- 3. What Motivated Russia’s Conquest of Central Asia: Economic Interests or Strategic Ambitions?

- 4. Did the Soviets Really ‘Create’ the Central Asian Nations?

- 5. How Were the Borders of Central Asia Drawn?

- 6. The Fight Over Tashkent

- 7. The Principles Guiding the Drawing of the Borders

- 8. Looking Back at the Great Game: Reality vs Myth

Was Central Asia a Colony?

In my view, there’s no doubt that during the tsarist period, both the steppe and Turkestani

But in terms of how the Russian Empire viewed Central Asia—both Turkestan and the steppe—I think it had much more in common with how the British understood their overseas possessions than with how Russian elites viewed older parts of their own empire. For example, the Volga region wasn’t seen as fundamentally separate from Russia itself. So for the Russian Empire, my answer is fairly straightforward—yes, it was a colonial empire.

Soviet Empire—or Something Else?

The Soviet period is more complicated. Many people have argued that Soviet modernity was itself a form of imperialism, that the Soviet Union was a classic colonial empire. That’s where I have some reservations. The argument that the USSR was simply a continuation of the tsarist colonial project has gained a lot of traction—especially outside Russia—after the 2022 invasion of Ukraine. At the same time, historians of Russia beyond its borders suddenly seemed to wake up to the fact that Russia carries a great deal of colonial baggage. Before 2022, this aspect was often underplayed, even with regard to the tsarist period.

In fact, American historiography, especially after the fall of the Soviet Union, became oddly sympathetic to the Russian Empire. I’ve had people tell me, quite seriously, that ‘Russia didn’t have colonies’, that it was different. That changed in 2022, when people were forced to rethink their assumptions.

Yakov Zavyalov. «The whole World shall be ours!». 1935 / Wikimedia Commons

So, while I think there was real continuity with the tsarist period, we also have to acknowledge the proclamations of equality, territorial autonomy, and especially the cultural projects that the Soviet Union undertook. You don’t really see that kind of investment or intentionality in other ‘classical’ colonial empires.

What Motivated Russia’s Conquest of Central Asia: Economic Interests or Strategic Ambitions?

Well, it’s not really an either/or question. The Russian conquest of Central Asia—whether of the Kazakh steppe or of Turkestan—was not driven purely by economic motives.

Vasily Vereshchagin. «By the Fortress Wall. "Let Them Enter». 1871 / Tretyakov Gallery

It’s easy to retroactively imagine some grand strategy behind Russian expansion, but in reality, much of it was improvised. The absence of a natural, easily defensible land border on the Eurasian steppe seems to have contributed to this never-ending expansion. By the 1840s and 50s, the Russian Empire had encircled the Kazakh steppe and quickly moved into Turkestan largely in pursuit of a secure frontier.

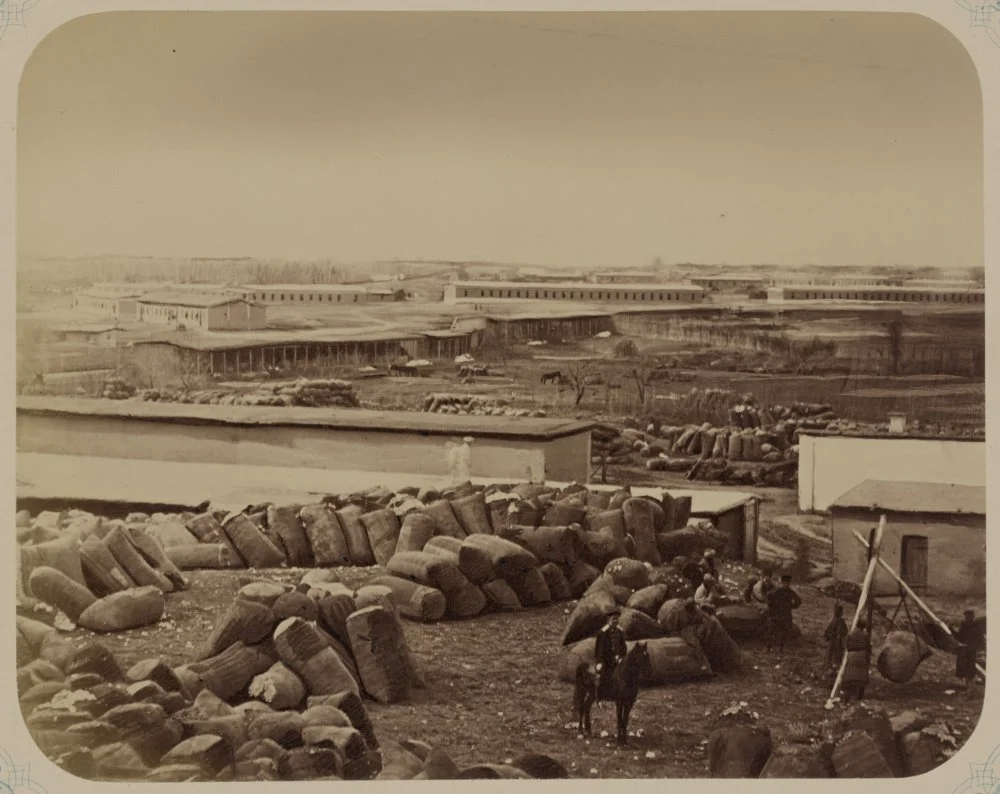

Cotton being packed and stored in bales during the Tsarist period in Central Asia. Syrdaria region, Tashkent. 1865 / Library of Congress

The usual argument is that the Russians wanted cotton, especially during the American Civil War, which cut off cotton supplies. But that argument doesn’t really hold up because the timing is off, and the Russian bourgeoisie, such as it was, lacked the political influence to push the militarized Russian state into a war for cotton. In the Soviet period, cotton cultivation became more important. It was grown as a cash crop, but mostly by small landholders as there were no plantations. Thus, once again, economic motives were secondary.

Did the Soviets Really ‘Create’ the Central Asian Nations?

On the one hand, the Soviet policy, not just korenizatsiia (indigenization) but the broader idea that in order to inculcate Soviet values and Soviet rule, political and linguistic boundaries should coincide, played an important role. However, this was also a response to how strong the various national movements had become in 1917–18. So in many ways, it was a preventative measure: to grant Soviet-style autonomy instead of real autonomy.

What I argue in Making Uzbekistan is that the Uzbek national project that ‘won out’ in 1924 wasn’t simply a product of the Soviet state. There were pre-revolutionary ideas of national identity that were strengthened and made more real after 1917, and in a very bizarre, complicated fashion, they actually won.

Negotiations with Basmachi leaders Kurshirmat and others. Fergana, 1921 / Wikimedia Commons

So, the notion that the Soviets simply created these nations from nothing is deeply problematic. There was already a sense of ‘Kazakhness’ before 1924. But in the West, that history is often read in a reductionist way—as if these countries were entirely artificial, created by Stalin to divide and conquer Central Asia. And that’s exactly what I’m arguing against. There were pre-1917 understandings of nationhood that shaped what became Uzbekistan, for instance, and the same goes for the others.

How Were the Borders of Central Asia Drawn?

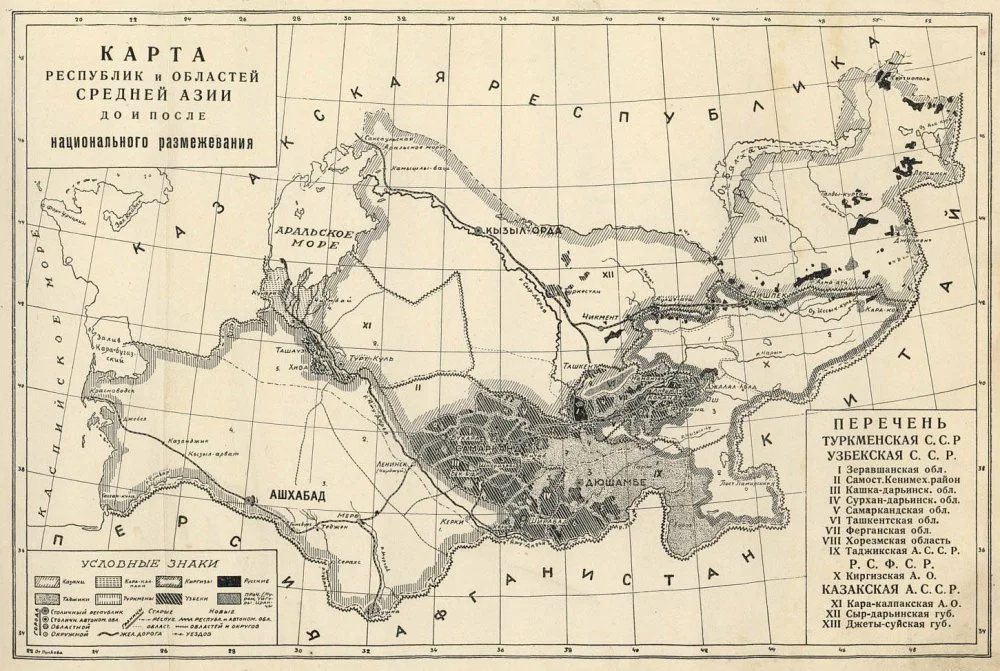

As for the national delimitation in Central Asia, there's no simple answer. First, the idea that political and administrative boundaries inside the Soviet Union should coincide with linguistic boundaries had already been established once the party decided, as early as 1919, that territorial autonomy was going to be the basis of the new Soviet state. In some ways, Central Asia was the last part of the Soviet Union where this principle was applied.

For the Soviets, the fact that Central Asia's boundaries were still the old administrative boundaries was problematic. The delimitation was a way of applying pan-Soviet principles to the region. The reason it had not been done earlier was that Soviet control over Central Asia was very weak. The idea of creating entirely new boundaries was unappealing to anyone in 1920, although Lenin had, in fact, written a note in June of that year stating, ‘Let's look into drawing new boundaries in Central Asia.’

Ultimately, the decision to draw new national boundaries and replace the three existing republics of Bukhara, Khorezm, and Turkestan came from Moscow. But when it was announced, much of the debate happened in Tashkent, among the Central Asian cadres.

V. Sadkov. «Long live the unity of the oppressed workers of the East with the workers of the whole world in the struggle for socialism!» Moscow, 1924 / Wikimedia Commons

There was the Sredazburo (Central Asian Bureau) of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, which was the plenipotentiary local organ based in Tashkent. It was an appointed body made up of people sent from Moscow, and it was where the debates took place.

We have the minutes of these meetings, which many researchers and I have studied. The debate was limited to members of the Communist Parties of the three republics. It was not a general debate among the intelligentsia, let alone the mass population. There were many questions: How many nations were there? How many groups could be recognized as a nation in Central Asia?

Initially, Moscow's suggestion was to create boundaries between three republics belonging to the Kazakhs (then called Kirgiz in Russian), Turkmens, and Uzbeks. The Uzbeks were, in many ways, considered the sedentary Muslim population of the region. Among the Kazakhs of Turkestan—mostly living in Semirechye but also in the Syr-Darya oblast—there was a strong sense of Kazakh identity, which was distinct from the Uzbeks. The same was true for the Turkmen elites. The debates, usually argued bitterly, revolved around which ‘subgroups’ belonged to which larger nationality—whether the Qaraqalpaqs or Kyrgyz were part of the Uzbeks or the Kazakhs—and where the boundaries should be drawn.

Some argued that the Kyrgyz were distinct from the Kazakhs and should have their own republic, as did the Qaraqalpaqs. They successfully convinced the Sredazburo, and ultimately the Politburo in Moscow, that they were indeed separate nationalities.

Meeting of the Presidium of the Central Executive Committee of the Kazakh SSR. September 1924 – April 1925 / From the collections of the Central State Archives of the Republic of Kazakhstan

The point is that there was no pre-existing consensus about how many distinct groups there were, and much less agreement on who occupied which territories. All of those decisions were really driven from below by local Muslim communists. Ultimately, the Sredazburo passed a resolution approving the plan, and then Moscow made some corrections. These were key issues where Moscow simply ruled by decree.

So, who drew the boundaries? Ultimately, they were approved by Moscow, but the process was not simply an imposition from there. The basic idea that there should be different republics—the communist leaders were happy with that. I see no dissent on that front, even if there might have been some unhappiness about where the boundary was drawn in some local cases. There was also quite a bit of local mobilization, where local party leaders mobilized support in different villages or auls to write petitions, arguing that the boundary, as it was drawn in 1924, should be changed.

The Fight Over Tashkent

Suddenly, the main debate about boundaries broke out between the Uzbeks and the Kazakhs, people who had often worked together in previous years but were now at odds. For instance, Sultanbek Khodzhanov, the Kazakh representative, wanted Tashkent to be the capital of the Kazakh republic. The population of the surrounding area was mostly Kazakh, and it was also a major cultural and administrative center. So this proposal was based on a different principle of territorial inclusion, but it caused a sharp division.

Meanwhile, the Uzbeks and those who would later become ardent Tajik nationalists formed a united front in 1924. There was a lot of backlash, but eventually, the Sredazburo passed a resolution that supported the Uzbek position that Tashkent should remain part of Uzbekistan.

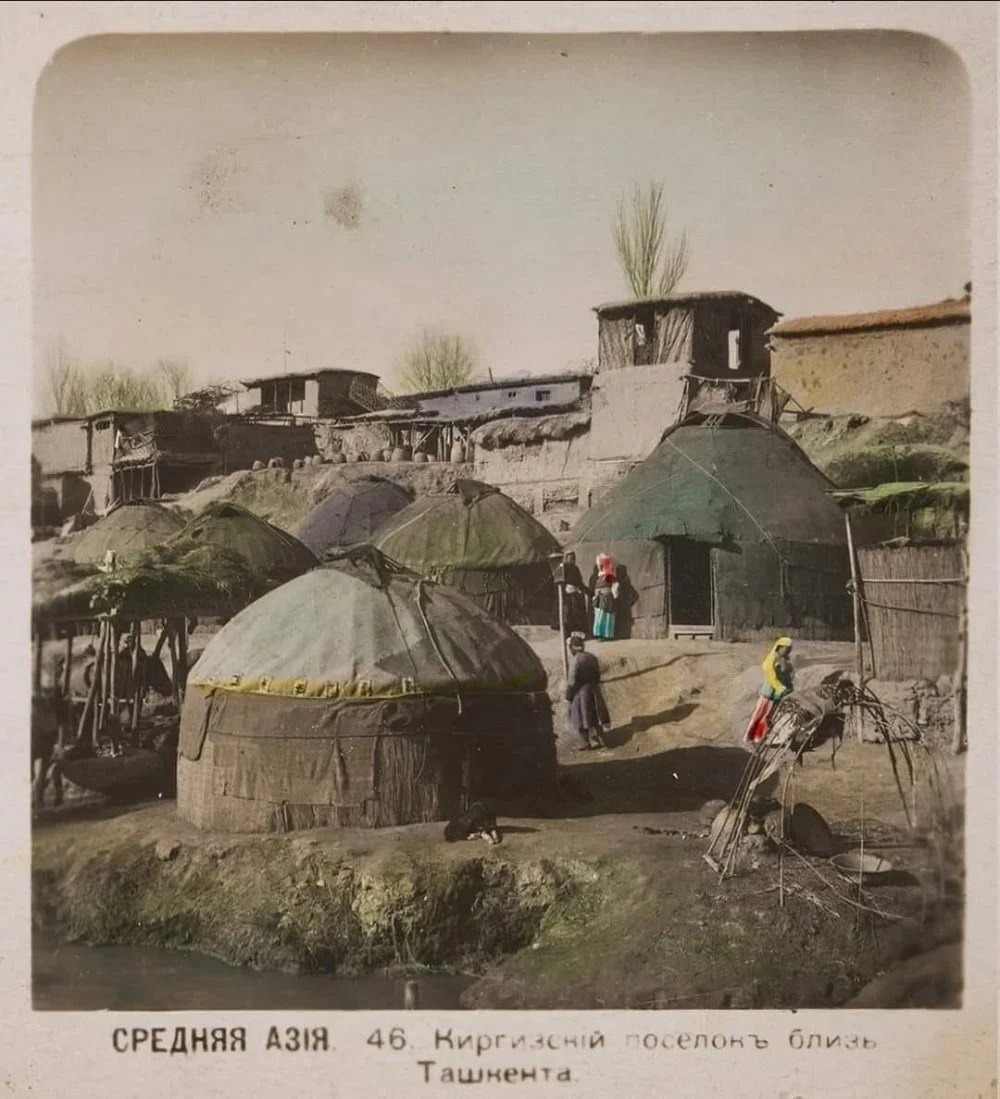

Kazakh (Kirghiz) village near Tashkent. Late 19th – early 20th century / Public domain / Public Domain

Immediately, large numbers of Kazakhs gathered in front of the Sredazburo office in what became a major public demonstration—likely in July 1924—demanding that the city be given to Kazakhstan. This serves as a clear example of public mobilization, even though the entire process was officially intended to remain a secret, internal party affair.

There were also other petition campaigns and pressure efforts, so that by August 1924, the party was already reprimanding Muslim communists for mobilizing public opinion, something that wasn’t supposed to happen at all. The final resolution on boundaries came in October 1924, dissolving the three preexisting republics and creating new ones.

Some Kazakh-majority areas of the former Turkestan and parts of Bukhara were added to the existing Kirgiz (Kazakh) Autonomous Republic. It meant that two different Kazakh political entities, one based in Turkestan (mainly from Semirechye) and the other based in the north, were now being merged into a single Kazakh political leadership. And this fusion of networks was actually one of the reasons Moscow decided that Kazakhstan should not become a full union republic (SSR) in 1924—unlike Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan.

The Principles Guiding the Drawing of the Borders

Ultimately, these republics were never meant to be purely ethnic. There were other principles involved, and one of them was that economic networks should remain integrated within a single republic and not be disrupted. That included irrigation networks but also other kinds of infrastructure. Not everything always aligned perfectly—sometimes, the principles even contradicted each other.

In Central Asia as well, the same logic was applied. That’s why Osh and Jalal-Abad, despite their mixed or Uzbek-majority urban populations, were given to Kyrgyzstan—because the countryside around them was Kyrgyz.

Map of the republics and regions of Central Asia before and after national demarcation from the book by K. Ramzin «Revolution in Central Asia». 1928 / Wikimedia Commons

The same principle could have applied to Tashkent. But it didn’t, and I think that’s because Tashkent was simply too important a center of Soviet power to be placed within a republic that would have only limited autonomy. At that point, Kazakhstan was still an autonomous republic within the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR), not a full union republic. Giving Tashkent to Kazakhstan would have meant reducing direct central (Moscow) control over the city. Besides, Tashkent had its own local party organization, particularly in the old city, and Stalin had reportedly grown suspicious of factionalism there, which also played a role.

As a result, when the first Congress of Soviets of Uzbekistan was held, it wasn’t even convened in Tashkent—it took place in Bukhara. In fact, the first capital of Soviet Uzbekistan was Samarkand, not Tashkent. That only changed in 1930, when the capital was relocated to Tashkent.

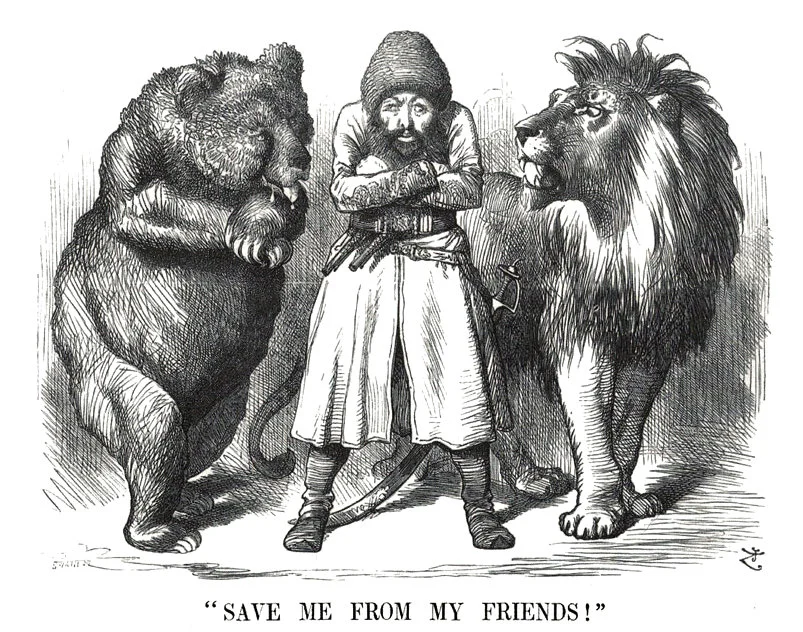

Looking Back at the Great Game: Reality vs Myth

As for the ‘Great Game’, its significance in events has been exaggerated. The entire literature of the Great Game is largely British imperial myth-making. It was shaped by generals and travelers who returned to Britain and wrote self-glorifying accounts of their ‘adventures’ in Central Asia.

The Great Game: the Afghan Emir Sher Ali Khan with his «friends» Russia and Great Britain. Published in «Punch» magazine, 30 November, 1878 / Wikimedia Commons

The British were mainly interested in defending their interests in India. Their goal was to surround it with a buffer of friendly states—not to conquer beyond the mountains. I’m not convinced the Russian army ever truly believed that if they didn’t get there first, the British would.

Unfortunately, some themes—like the Silk Road, the Great Game, or the idea that Stalin personally created the map of Central Asia—are just too seductive. They’re neat, they’re dramatic, and no matter how much archival evidence you provide, these stories continue to dominate public narratives.